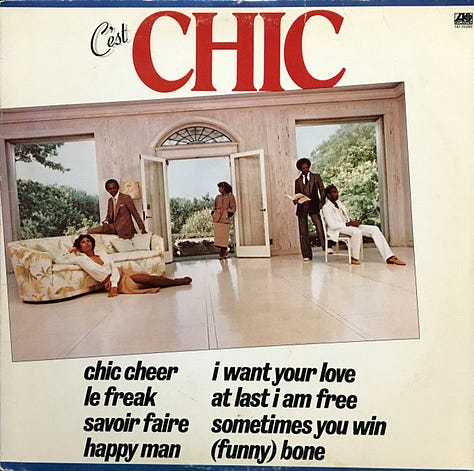

C’est Chic (1978) – Album Analysis

Background & History

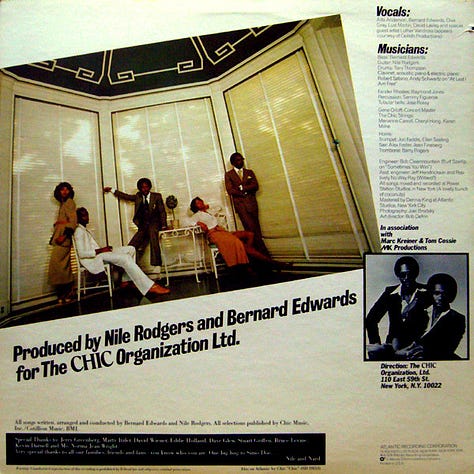

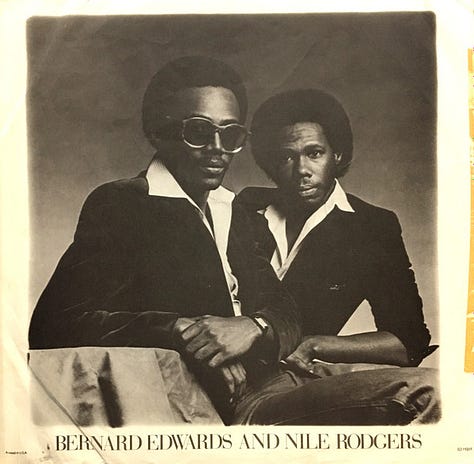

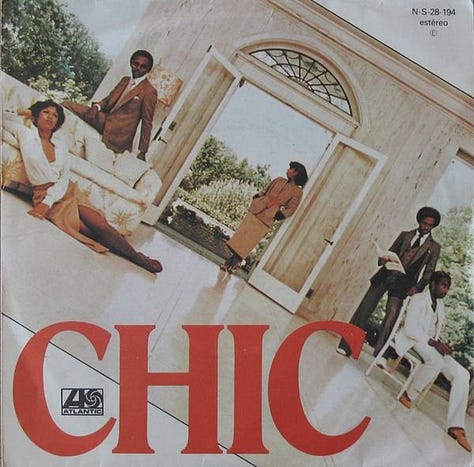

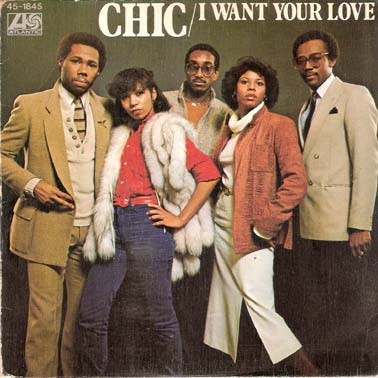

Chic’s second studio album, C’est Chic, was released in August 1978 at the height of the disco boom. The band – led by guitarist Nile Rodgers and bassist Bernard Edwards – had already scored hits with their 1977 debut (Chic) and emerged as a new force in dance music. With C’est Chic, Rodgers and Edwards sought to build on that momentum, refining their blend of funk and disco with a sophisticated image and sound. The duo famously drew inspiration from chic European influences (even naming their production company “The Chic Organization Ltd.”) and modeled themselves as a “cut above” other disco acts, dressing in stylish suits and running the band like a business. This cultivated image reflected their ambition to be seen not just as a dance band but as savvy musical trendsetters.

The context of C’est Chic’s creation was the peak of the disco era – Saturday Night Fever had made disco mainstream, and Chic was eager to deliver upscale dance music to this thriving scene. One key inspiration behind the album’s biggest hit came from a real-life nightclub drama. On New Year’s Eve 1977, Rodgers and Edwards were invited to the exclusive Studio 54 in New York by singer Grace Jones, but were denied entry at the door (Jones forgot to notify the club staff). Frustrated, they went back to Rodgers’ apartment and jammed on a riff, initially chanting an expletive-laden refrain (“Fuck off!”) to vent their anger . This riff evolved into “Le Freak”, with the chorus cleaned up to the now-iconic “Freak out!” line. Thus, a moment of exclusion was transformed into creative gold, channeling their anger into what would become a historic disco anthem.

At the time of recording C’est Chic (at New York’s Power Station studio in 1978 ), the band’s lineup was in flux. Original lead singer Norma Jean Wright had departed for a solo career, so Chic’s vocal duties fell to Alfa Anderson and Luci Martin – sometimes dubbed the “funky divas” for their sultry voices. Backing vocals were bolstered by notable session singers like Luther Vandross (years before his own stardom). The band’s core remained Rodgers on guitar, Edwards on bass, and Tony Thompson on drums – a powerhouse trio who had honed their chemistry playing everything from R&B club gigs to rock jams. In fact, Rodgers and Edwards had been pulling double duty in the mid-70s: by day they were disco session players, by night they jammed in rock/new-wave outfits with Thompson. This diverse experience gave them a wide musical vocabulary and tight musicianship that would inform C’est Chic’s sound.”

Production & Style

On C’est Chic, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards perfected a production style that was polished yet irresistibly groovy – a “sleekly elegant variation” of disco, as one contemporary reviewer described it. The album’s sonic signature is defined by Edwards’ rubbery, melodic bass lines locking in with Thompson’s precise drum grooves, while Rodgers’ trademark rhythm guitar “chucking” adds a percussive shimmer on top. This rhythm section created a cool, controlled funk that some have called “cool to the point of glacial, rhythmic to the point of metronomic”. In other words, Chic’s playing was impeccably tight and consistent – the product of careful arrangements and countless hours in the studio perfecting each groove.

The instrumentation and production techniques on C’est Chic were notably lush. Rodgers and Edwards, who produced the album themselves (under the Chic Organization banner), incorporated orchestral elements that added sophistication to the dance tracks. The Chic Strings – a trio of string players led by concertmaster Gene Orloff – adorn songs like “I Want Your Love” with sweeping violins that accentuate the drama. Horn players (including trumpet virtuoso Jon Faddis) layer bright bursts of brass on the funkier cuts. These string and horn arrangements gave the album a rich, layered texture that distinguished Chic from rawer funk bands. At the same time, the production never loses sight of the rhythm. Engineer Bob Clearmountain captured Thompson’s drums with a crisp clarity (the Power Station studio was famed for its drum sound), ensuring that even with strings and horns in the mix, the beat stayed front and center. Every track has a clean, well-balanced mix – a hallmark of Chic’s meticulous production.

Rodgers and Edwards also employed subtle studio touches to enhance the album’s atmosphere. Notably, C’est Chic is framed like a live show – it opens and closes with the ambient sound of a crowd, as if bookending the album with the feel of a concert. There’s a “faux live audience” effect at the beginning of the first track and again in the finale . This was a production gimmick common in late-’70s disco albums (to give the impression of a party vibe), and Chic use it to make C’est Chic feel like an immersive experience. The album effectively plays out “like a show,” starting with an upbeat overture and ending with a playful encore . Despite these theatrics, the sound is never cluttered – the arrangements leave plenty of space for the all-important groove. Rodgers’ guitar scratches, Edwards’ bass thumps, Thompson’s steady 4/4 kick drum, and the female vocal harmonies are all distinct in the mix, a testament to Chic’s high production standards. Critics and fans have since marveled at how well C’est Chic was recorded; in modern remasters, the audio fidelity remains impressive, with one reviewer calling it “utterly magnificent, with a perfect mix and soundstage”.

Stylistically, C’est Chic balances dancefloor anthems with more soulful, introspective moments, showcasing Chic’s range within the disco/funk genre. Up-tempo tracks ride relentless grooves meant for dancing, while slower tunes incorporate an R&B feel verging on quiet storm balladry. This variety was somewhat unusual for a disco album, as Chic wove in moods of melancholy and sophistication alongside the party jams. The polished production and urbane style of C’est Chic would become hugely influential – the “distinctive Nile Rodgers/Bernard Edwards sound” here, with its blend of funk guitars, slick bass, and strings, later inspired artists from new wave to hip-hop to house music. In short, Rodgers and Edwards set a new bar for production in dance music, melding the raw funk roots of disco with a refined studio craft.

Track-by-Track Analysis

“Chic Cheer”

The album kicks off with “Chic Cheer,” a celebratory opener that sets the tone. It literally begins with crowd noise – the sound of an excited audience – before the band’s groove drops in . This faux-live intro creates the illusion that Chic is taking the stage for a live performance. Once the cheers subside, we’re met with an “intoxicating” mid-tempo funk rhythm driven by Edwards’ syncopated bass and a steady four-on-the-floor drumbeat. There isn’t a traditional sung verse/chorus structure here; instead, the track is built on vocal chants and instrumental jamming. The female vocalists (and possibly the whole band in unison) repeat phrases like a call-and-response cheer – essentially hyping up the “Chic” name. As the title suggests, it’s like a cheerleading chant for the band itself, with the word “Chic” punctuating the funky groove. Rodgers’ guitar riffs slice through with percussive clarity, and brief horn stabs accent the rhythm. The overall vibe is of a festive intro – Chic Cheer feels like a warm-up number to get the listener dancing and announce that Chic is here.

While not as melodically strong as some later tracks, “Chic Cheer” serves its purpose in the album sequencing. One reviewer noted you’re “unlikely to seek ‘Chic Cheer’ out on its own” but as an album opener it’s “perfect” for setting the mood . The groove is infectious and establishes Chic’s core elements: tight rhythm section, playful group vocals, and a party atmosphere. It also subtly nods to the band’s confidence – they are literally cheering themselves, inviting everyone to join the celebration. In terms of significance, “Chic Cheer” might not be a radio hit, but it underscores Chic’s emphasis on groove over traditional songcraft. (Robert Christgau once remarked that Chic’s “hooky cuts are more jingles than songs”, and “Chic Cheer” exemplifies that jingle-like repetition.) It’s a fun, funky prologue that leads us straight into the album’s most famous song.

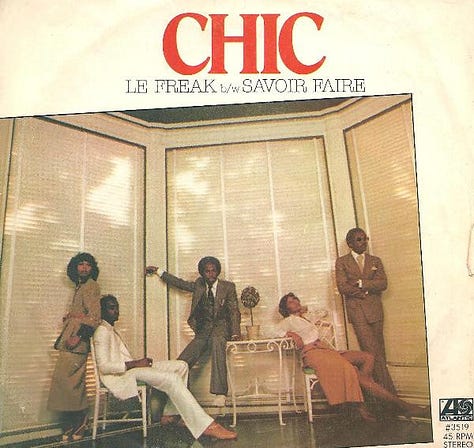

“Le Freak”

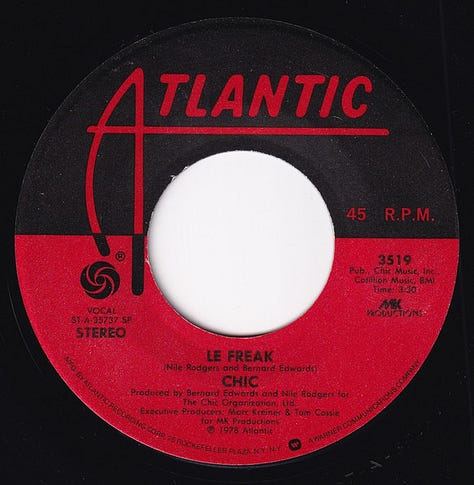

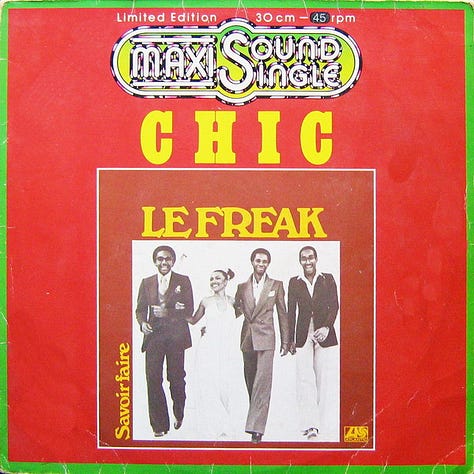

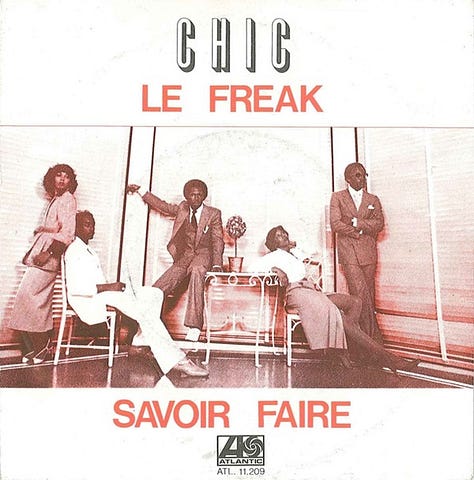

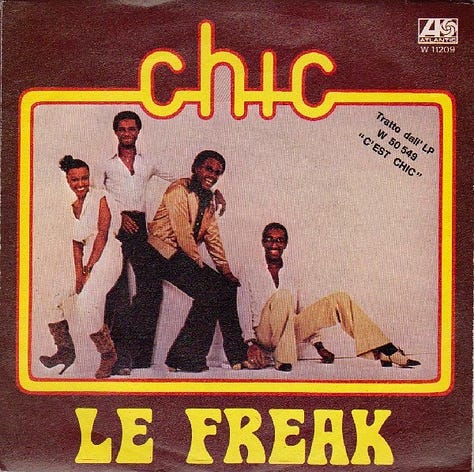

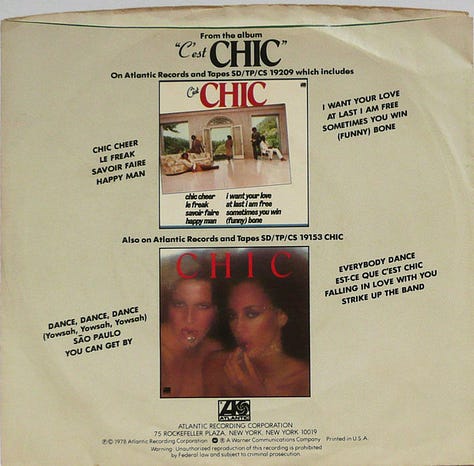

“Le Freak” is C’est Chic’s crown jewel and Chic’s signature song. Opening with Nile Rodgers’ scratchy guitar and that famous count-in, it immediately commands attention with the refrain “Aaahh, freak out!” – a call that became legendary on dance floors. Musically, “Le Freak” is Chic 101: a perfect distillation of disco-funk elements. Bernard Edwards’ bassline is chunky and hypnotic, forming the backbone of the song, while Tony Thompson’s drums keep a steady, driving beat tailored for clubs. The arrangement is cleverly layered – during verses, the groove pares down to bass, drums, and guitar chanks, leaving space for the vocals, then the choruses explode with string flourishes and the emphatic “Freak Out/Le Freak, c’est chic” gang vocals. Alfa Anderson and Diva Gray handle the lead vocal lines, delivering cool, “airy” vocals atop the bass-driven groove . Lyrically, the song is an invitation to dance: “Just come on down to the 54” directly references Studio 54 and urges listeners to join the party. This is ironic given the song’s genesis – born from Chic’s exclusion from that very nightclub – yet the lyrics were flipped to become utterly positive and inclusive. Rather than saying “F off” to the club, Chic chose to say “freak out” to the world , birthing an anthem of joyous release.

The backstory of “Le Freak” adds depth to its otherwise celebratory lyrics. Rodgers and Edwards wrote it after being turned away at Studio 54, initially with the tongue-in-cheek refrain “Fuck off!” as a private joke . They later revised it to the radio-friendly “Freak out!,” and even played with French in the title (Le Freak) to match the band’s chic image. The result was magic – the song captured the irresistible urge to dance, and listeners responded in a big way. Upon release in late 1978, “Le Freak” became a monster hit: it reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and remarkably returned to the #1 spot three separate times, for a total of six weeks on top . This feat made “Le Freak” the first song in history to hit #1 on three different occasions. It ultimately sold over 6 million copies in the US alone , becoming (at the time) the biggest-selling single in Atlantic Records’ history . In the UK, it peaked at #7, also a strong showing. The song dominated discos, R&B charts (it was #1 on the Soul chart as well), and crossed over to mainstream pop listeners worldwide. Billboard later ranked it the #3 song of 1979 year-end , and decades on, its legacy endures – in 2015 the original recording of “Le Freak” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame , cementing its status as one of the all-time classics.

Critically, “Le Freak” earned praise for its musical craft. The trade paper Cash Box in 1978 highlighted its “solid bass work and airy vocals” as key strengths, calling it a “handclapping disco song” sure to fill dance floors . Indeed, Edwards’ bass is often singled out: his popping bass line in “Le Freak” is a masterclass in groove, frequently imitated by others. Rodgers’ guitar, while largely playing rhythmic chords, also provides a catchy hook (the scratchy riff that opens the track). And the Chic Strings add drama, especially in the breakdown section where the strings scale up before the final chorus – a moment that always electrifies crowds. The song’s “Freak out!” refrain has become part of pop culture lexicon, immediately recognizable even to those who’ve never set foot in a disco. In essence, “Le Freak” is both a product of its era and a timeless dance anthem. Its inclusion on C’est Chic propelled the album’s success, and to this day, the track’s theme of letting loose on the dance floor continues to resonate. Simply put, if C’est Chic is an event, then “Le Freak” is the peak of the night’s party – an evergreen invitation to dance away your cares.

“Savoir Faire”

After the exhilaration of “Le Freak,” the album downshifts in tempo and intensity with “Savoir Faire.” This track is a stylish instrumental (no lead vocals are present) that spotlights Chic’s musical finesse. “Savoir Faire” – a French phrase meaning “know-how” or finesse – is an apt title for a piece that oozes smooth confidence. It opens with a mellow, almost symphonic mood: strings sweep gently as a laid-back beat kicks in. Nile Rodgers’ guitar takes the lead melody here, playing a lyrical theme with a slight jazz flavor over the steady rhythm. His guitar tone is clean and singing, demonstrating a different side of his playing beyond the percussive funk chops. One reviewer describes Rodgers’ guitar work on this tune as “simply exquisite”, and indeed “Savoir Faire” often gets praise as a showcase for his understated lead style. The track blends disco, funk, and lush pop instrumental elements – one can hear hints of jazz and even easy-listening soul in the mix. Rhythmic handclaps and a conga-like percussion can be heard in the background, giving it a gentle groove. The Chic Strings add a romantic touch, punctuating Rodgers’ guitar lines with sustained chords. About midway, the arrangement swells as the strings take a more prominent role, almost like a mini-concerto between guitar and orchestra.

“Savoir Faire” serves as a breather on the album, creating a glamorous atmosphere. It’s not designed as a dancefloor filler; instead, it evokes the image of a chic lounge or perhaps a late-night comedown after heavy dancing. The inclusion of an instrumental track also underlines Chic’s musicianship – they weren’t just about catchy vocals and hooks, but could hold interest with pure instrumentation. The recording quality on this track is especially crisp, highlighting every nuanced guitar lick and violin phrase (fans of audiophile sound often cite this cut). Retrospectively, listeners have called it one of their “all-time favorite Chic songs” despite (or because of) its departure from the standard disco formula. The tune’s elegant vibe would later make it ripe for sampling by hip-hop artists looking for silky grooves (for instance, elements of “Savoir Faire” have been sampled in tracks by rappers like Rick Ross) – a testament to the track’s enduring cool. Positioned as the third track, “Savoir Faire” effectively broadens the album’s emotional palette, adding a touch of sophistication and proving that even without words, Chic’s music could speak volumes with style.

“Happy Man”

Closing out side one of the LP is “Happy Man,” a funk-infused mid-tempo song that brings vocals back into the mix. Uniquely, the lead vocal on “Happy Man” is handled by Bernard Edwards (Chic’s bassist). Edwards’ vocal style is more restrained and conversational compared to the female singers; here he delivers the lyrics in a cool, laid-back tone. The song itself is upbeat in message – as the title suggests, it’s about the contentment of a man who’s found love or personal peace (“I used to be lonely, till I learned about living alone…” the lyrics express a turn from loneliness to happiness). Despite the positive theme, “Happy Man” carries a slightly melancholy undertone in its melody, a common trait in Chic’s songwriting where even celebratory tracks have a layer of sophistication.

Musically, “Happy Man” rides on a groovy, mid-tempo funk rhythm. The bassline is prominent (as you’d expect with Edwards singing – he underpins his vocals with funky bass flourishes), and the drums have a steady, head-nodding pulse. Rodgers’ guitar riff in this track is more rhythmic accent than lead, chopping chords on the off-beats that give the song a gentle bounce. The chorus brings in the female backing vocals harmonizing the title refrain “Happy man, that’s me,” reinforcing the hook. Strings swirl in the background especially during the chorus, adding a lush backdrop to the otherwise earthy groove. There are also playful horn interjections – little trumpet and sax riffs that respond to the vocals. The combination of these elements makes “Happy Man” feel like a bridging piece between the album’s two halves: it’s got enough rhythm to keep dancers interested, but it’s also somewhat reflective in tone, perhaps prepping the listener for the deeper cuts on side two.

Critically, “Happy Man” didn’t generate as much commentary as the singles, but it’s often appreciated by fans as a solid album track. One modern reviewer simply called it “a great song!” that brings us back to the dance floor after the chill of “Savoir Faire” . Indeed, coming after the instrumental, “Happy Man” reintroduces vocals and that party feel. It’s also notable for showcasing Bernard Edwards as a vocalist – something Chic did sparingly. Edwards’ smooth baritone adds variety to C’est Chic, since most other songs feature female leads. This track’s “contentment” theme, wrapped in a warm groove, contributes to the album’s emotional balance. While not a hit on its own, “Happy Man” reinforces the album’s concept of moving through different moods while maintaining a unified Chic sound. By the time it fades out, the listener has been taken from the high-energy peak of “Le Freak” down to a chilled instrumental and up again to a feel-good groove, perfectly setting the stage for side two.

“I Want Your Love”

Side two opens with “I Want Your Love,” the album’s second big hit and one of Chic’s most acclaimed songs. Clocking in at nearly 7 minutes, the album version of “I Want Your Love” is an extended dance epic that epitomizes late-70s disco sophistication. The track begins with a memorable introduction: a swirling tapestry of strings that crescendo dramatically, joined by a syncopated horn motif, before the rhythm kicks in. This intro immediately signals a shift – it’s lush, dramatic, and dripping with yearning. As the groove settles, Alfa Anderson’s sultry lead vocal enters, delivering the opening line “I want your love, I want your love” with a mix of longing and poise. Lyrically, it’s a straightforward love song about desire and the craving for reciprocation in a relationship. Anderson’s vocal performance is often lauded as “stunning and perfectly suited to the recording” – she conveys vulnerability and passion, elevating the song’s emotional impact. In the chorus, her voice is multitracked into harmonies, and backed by the other vocalists, creating a rich choral effect singing “I want your love, I need your love.”

Musically, “I Want Your Love” is driven by one of Edwards’ most infectious bass grooves. The bass line is propulsive yet muted, locking into a tight pocket with Thompson’s drums. Nile Rodgers’ guitar plays a subtle role here – mostly skittering in the background to support the rhythm – as the spotlight often shifts to the orchestrations. The Chic Strings have a star turn: the string section plays swirling lines and a distinctive riff that repeats throughout (this riff has become iconic in its own right, frequently sampled in later songs). There’s also a prominent horn arrangement; in the breakdown, saxophones and trumpets kick in with punchy syncopations that add funk and drama. During instrumental breaks, a sax solo embellishes the groove, while the rhythm section never lets up the hypnotic thump. The production layers elements masterfully, building intensity over the song’s length – by the final choruses, all elements (strings, horns, vocals, rhythm) converge in a powerful crescendo.

Upon its release as a single in early 1979, “I Want Your Love” proved Chic was no one-hit wonder. It reached #7 on the Billboard Hot 100 and #5 on the R&B chart, becoming a sizable hit in its own right. In the UK it climbed even higher, peaking at #4 . The song’s success cemented the group’s superstar status and showcased their more romantic, orchestral side. Critics appreciated the song’s craft; Billboard praised its catchy melody and Chic’s trademark groove craftsmanship (contributing to the band’s “new star status” following “Le Freak” ). In retrospect, many consider “I Want Your Love” one of Chic’s finest moments – it’s frequently cited in “best disco tracks” lists for its blend of soulful yearning and dancefloor appeal. Modern reviews call it “one of the best songs Chic ever recorded” and a “shimmering gem” of the album. Indeed, the track’s influence has carried on: the elegant disco strings and bassline have been sampled by house music producers (Detroit’s Moodymann built a cult favorite track out of it in the ’90s), and even pop superstar Lady Gaga was drawn to “I Want Your Love,” recording a cover decades later. Ultimately, the song’s enduring popularity lies in how beautifully it marries heartfelt emotion with the physical urge to dance – listening to those yearning vocals over that relentless groove, one can’t help but sway along with feeling.

“At Last I Am Free”

Perhaps the biggest surprise on C’est Chic is “At Last I Am Free,” a poignant ballad that slows the tempo way down and reveals a very different side of Chic. At 7+ minutes, this track is a languid, soulful R&B ballad that some have called the emotional “cracked soul” of the disco era. Alfa Anderson takes the lead vocal here, and her performance is tender and haunting. The lyrics speak to liberation and heartbreak in equal measure – “At last I am free, I can hardly see in front of me” goes the chorus, a line that conveys relief but also vulnerability. While on the surface it could be about the end of a bad relationship (finally being free), the ambiguity of the words gives it a universal resonance. The way Anderson delivers the chorus, with layered harmonies and an almost gospel-like sincerity, imbues the song with deep feeling. One critic noted that the harmonies are “out-of-this-world” and “simply beautiful,” especially on the chorus . Indeed, when those voices converge on “free…free…free” it’s a spine-tingling moment, unexpected on a Chic record known for upbeat tunes.

Musically, “At Last I Am Free” is built on a slow, dreamy groove. Tony Thompson’s drums play a soft, unhurried 4/4 beat with a gentle hi-hat tick and restrained kick – the antithesis of the driving disco beats elsewhere on the album. Edwards’ bass is subdued, almost minimalist, offering sparse low-end notes that anchor the chords without any busy funk lines. Rodgers’ guitar work is subtle arpeggios and chord strums that ring out in the wide spaces of the mix. The instrumentation leaves plenty of room for the vocals and the atmosphere. Keyboards (electric piano) and the Chic Strings fill in the background with warm pads. The overall arrangement has a hazy, quiet-storm feel – you might imagine low lights on an empty dance floor, the party over and introspection setting in. Midway through the track, there’s a gentle instrumental interlude where the strings take a more pronounced role, almost classical in their sadness. Unlike the formula of disco ballads that still aim for a big climax, “At Last I Am Free” stays restrained throughout, emphasizing a meditative mood.

When C’est Chic was released, a ballad like this on a disco album was unexpected. The Los Angeles Times at the time actually criticized the album’s slower numbers as “plodding R&B ballads” – perhaps referring to this track – but over time “At Last I Am Free” has been critically reappraised. Many now see it as a highlight that showcased Chic’s versatility and depth. The song’s emotional rawness struck a chord with listeners beyond the disco context. In fact, “At Last I Am Free” went on to have a second life through cover versions: most notably, British artist Robert Wyatt covered it in 1980, stripping it down to an even starker piano-and-vocal rendition that highlighted the song’s melancholy poetry. Wyatt’s cover, released on the Rough Trade label, recast the song as a left-field art-soul piece and has been described as “moving” and “poignant,” showing how strong the songwriting is at its core. (Years later, artists like Elizabeth Fraser of Cocteau Twins and others would also interpret the song, attracted by its mood.) Such covers and critical essays have noted that “At Last I Am Free” revealed a cracked soul beneath disco’s glittery surface, suggesting it carried an undertone of the uncertainties and hopes of its era. In the context of the album, the track provides a beautiful, introspective centerpiece – after the extroverted first half, this song pulls the listener inward. By ending the chorus on the word “free,” drawn out with those rich harmonies, Chic created a moment of catharsis that resonates emotionally. It stands as proof that behind the chic façade and dancefloor polish, Rodgers and Edwards were capable of profound, heartfelt songwriting.

“Sometimes You Win”

Following the heavy emotions of the previous track, “Sometimes You Win” picks the tempo back up, returning to Chic’s funky disco wheelhouse. This song is a mid-to-up tempo groover that thematically offers a pragmatic take on life and love: as the title says, sometimes you win, sometimes you don’t – a gentle reminder of life’s ups and downs. Bernard Edwards and Alfa Anderson share lead vocals on this track (both are credited for lead), which suggests they trade lines or verses. Indeed, listening to it, Edwards often sings the verses in his laid-back style, while Anderson joins in strongly on the choruses. The interplay gives the song a fun dynamic, almost like two characters reflecting on a relationship or the game of love. The lyrics use gambling metaphors (“you take a chance on love”, “sometimes you win, sometimes you lose”), aligning with the disco-era tendency to equate nightlife and romance with games of chance. Despite the potential for cynicism, the tone of the song is upbeat and optimistic – it acknowledges losses but celebrates the wins.

Musically, “Sometimes You Win” is an infectious disco-funk track. Tony Thompson’s drums are back in full-force disco mode: a steady driving beat with energetic hi-hat patterns that compel you to move. Edwards’ bass line is active and catchy, one of those bubbling bass grooves that’s both rhythmic and melodic. Rodgers layers funky chord chops and a few catchy single-note guitar licks. The female background singers punctuate the groove with repeating lines (echoing the title and responding to Edwards’ lines). The chorus is memorable – “sometimes you win, sometimes you lose” sung in a tight harmony that’s easy to sing along with. Chic’s trademark strings and horns are present but a bit more subdued here than on “I Want Your Love”; they add flourish without dominating, perhaps a flourish of strings around the chorus to lift it. Overall, the arrangement is bright and brassy, keeping the energy up. There’s a short break where the instrumentation pares down to percussion and bass, giving a mini “breakdance” moment before everything swells back – a common disco technique to momentarily strip down the groove and then reintroduce it to greater effect.

“Sometimes You Win” may not be as famous as the singles, but it’s often highlighted as a fan favorite deep cut. It has the kind of groove that “compels your body to move involuntarily” – as one recent reviewer put it, the song connects so directly to the listener’s dancing instinct that you’ll find yourself moving without realizing. In the flow of the album, it smartly lifts the mood after the somber “At Last I Am Free,” bringing the listener back into an upbeat space. Thematically, placing “Sometimes You Win” after a song about newfound freedom could be seen as Chic saying, “Alright, pick yourself up – life goes on, and there’s joy to be found.” It maintains the album’s narrative of emotional ebb and flow. From a legacy standpoint, “Sometimes You Win” is a reminder of Chic’s consistency – even their non-singles were tight, danceable, and cleverly composed. The track’s title also proved somewhat prophetic for the band; with C’est Chic, they mostly won (critical and commercial success), but as the next year’s disco backlash would show, sometimes you lose – an irony that makes this upbeat song slightly bittersweet in hindsight.

“(Funny) Bone”

C’est Chic concludes with “(Funny) Bone,” a short, mostly-instrumental piece that acts as a playful encore for the album. “(Funny) Bone” is essentially a funky jam led by a Moog synthesizer solo. It begins with the return of the crowd noise – the fake audience ambience comes back, making it sound as if Chic is returning to the stage for one last number. Then the music kicks in: a fast-paced, swinging disco-funk groove with a prominent synthesizer riff that immediately grabs attention. The track is entirely instrumental apart from perhaps some crowd exclamations, and it’s also quite short (around 3:40). The term “Funny Bone” suggests a sense of humor or something lighthearted, and indeed the music feels a bit like Chic having fun and cutting loose without the formality of a structured song. The Moog synth takes the “lead vocal” role here – it noodles and doodles a quirky melody on top of the tight rhythm section. You can hear the keyboardist (likely Raymond Jones or Andy Schwartz, who handled synths) improvising runs and bends, giving the track a slightly offbeat, comic vibe (hence the “funny”). Underneath, Rodgers, Edwards, and Thompson keep a fast, driving groove – it’s funky, with the guitar and bass doing quick hits (somewhat reminiscent of a chase scene music!). Horns join in sporadically with punchy blasts, almost like they’re punctuating a joke. The crowd noise may fade in and out, as if people are clapping along or reacting.

“(Funny) Bone” serves as an upbeat finale, leaving the listener on a high note. It doesn’t aim for the polished grandeur of earlier tracks; instead it feels intentionally a bit raw and spontaneous. One interpretation is that Chic wanted to close the album reminding everyone that they are, at heart, a band of musicians who love to jam. After all the elegant arrangements and emotional highs, here’s a straightforward funky jam to send you off. A reviewer noted that it’s a “solid closer” that makes you want to “play the record again”, even if the faux-audience gimmick at the start of the track could have been handled differently. Indeed, by reprising the live crowd sound at the end, Chic bring the album full-circle. If “Chic Cheer” was the overture, “(Funny) Bone” is the encore – and having the crowd fade in at the beginning of both tracks creates a neat frame around the album’s runtime.

In terms of significance, “(Funny) Bone” might not stand out on its own. It’s an unusual choice that shows Rodgers and Edwards weren’t afraid to break the typical album mold. The track’s Moog solo also nods to the increasing presence of electronics in dance music – it was 1978, and the synthesizer was becoming a staple of funk and disco (foretelling the synth-driven direction of ‘80s dance). By titling it “Funny Bone,” Chic might even be winking at the listener – after an album exuding class and chicness, they end with something tongue-in-cheek and groovy. As the last notes (and perhaps crowd cheers) of “(Funny) Bone” fade out, the C’est Chic experience concludes not with a dramatic bang, but with a sly grin and a funky shrug. It encourages the listener to flip the record back to side one – because the show is over, but the groove never really ends.

Commercial Performance

C’est Chic was a major commercial success, becoming the most successful album of Chic’s career. In the United States, the album rode the wave of its hit singles to achieve impressive chart placements. It peaked at #4 on the Billboard 200 albums chart and #1 on the R&B Albums chart, holding the top R&B spot for an astounding 11 weeks. During a time when the charts were saturated with blockbuster soundtracks and pop/rock acts, C’est Chic’s performance solidified Chic as disco superstars. By January 1979, it was such a force that Billboard magazine named C’est Chic the 1979 R&B Album of the Year, as it was the top-selling soul/R&B album on their year-end review. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) certified the album Platinum, denoting over a million copies sold in the U.S. – a rare feat for a disco album (many disco acts were singles-driven). In fact, C’est Chic became one of the few disco albums to go platinum during the era , underscoring its crossover appeal and strong sales.

Internationally, the album also fared well. In the United Kingdom, C’est Chic reached #2 on the UK Albums Chart, buoyed by the popularity of “Le Freak” and “I Want Your Love” in Europe. It earned a Gold certification in the UK for solid sales. Across Europe, the record hit the top 10 in countries like the Netherlands and Germany (peaking at #9 and #10 on those national charts, respectively). It even charted in Scandinavia (Top 20 in Norway and Sweden), showing that Chic’s grooves had global reach. The single “Le Freak” was the locomotive of the album’s success. That song topped the US Hot 100 (and R&B and Disco charts) and ultimately sold around 6 million copies in the U.S. alone – one of the best-selling singles of all time up to that point. Its massive popularity undoubtedly drove album sales; many buyers picked up C’est Chic to own “Le Freak,” then discovered the rest of the album’s riches. The second single “I Want Your Love” also performed strongly, hitting #7 on the Hot 100 and #5 on R&B in mid-1979, as well as top 5 in the UK . Having two big hits gave the album longevity on the charts.

Upon release, C’est Chic received substantial attention and airplay. “Le Freak” was ubiquitous on radio and in clubs in late 1978, and by early 1979 “I Want Your Love” kept Chic on the radio. The album itself found favor not just with disco audiences but with a broader pop market, thanks to Atlantic Records’ promotion and Chic’s growing reputation. It’s worth noting that C’est Chic achieved its success just before the disco backlash (which peaked in mid-1979 with events like the infamous Disco Demolition Night). So, in many ways C’est Chic represents the zenith of disco’s commercial power – it dominated charts in the first half of 1979 when disco was still red-hot, and it stood alongside Saturday Night Fever and Donna Summer’s works as one of the genre’s flagship releases.

Years later, the album’s sales and impact are still remembered. Rhino Records (in a 2024 retrospective blurb) noted that upon release C’est Chic “was named R&B Album of the Year by Billboard… the Platinum-selling C’EST CHIC remains très magnifique” , underlining that it hasn’t lost its shine. In summary, from a commercial standpoint, C’est Chic was an unequivocal triumph: a platinum, chart-topping album that made Chic a household name. It proved that an album deeply rooted in disco could both churn out hit singles and also sell strongly as a complete LP – a testament to the record’s quality and Chic’s star power during the disco era’s peak.

Cultural Impact & Legacy

C’est Chic has left an enduring cultural impact, both within the disco genre and on popular music at large. Released as disco was approaching its apex, the album captured the spirit of an era – the glitzy nightlife, the freedom of the dance floor, and the blending of musical sophistication with raw funk energy. In the years since, it has come to be regarded as one of the quintessential disco albums. Some retrospectives go so far as to call C’est Chic “one of the best albums of the ’70s”, noting that its disco label was in some ways a red herring – the album’s appeal and influence transcend the disco tag. Indeed, Chic’s cool, polished sound on this record was as much a precursor to ’80s R&B and dance-pop as it was a product of late-’70s club culture. The album is often lauded for being timeless: even decades later, tracks like “Le Freak” and “I Want Your Love” still fill dance floors and are covered or sampled by new artists, proving the music’s longevity. As one modern writer put it, “some albums define a generation, even a genre, and C’est Chic is one such release that sounds as fresh today as it did in 1978”.

One of the most direct legacies of C’est Chic is its influence on other musicians. The distinctive Chic sound – funky rhythm guitar, grooving bass, elegant strings – became a template that many sought to emulate. Contemporary R&B and funk bands in the late ’70s took cues from Chic’s arrangement style, and when disco evolved into post-disco and boogie in the early ’80s, the imprint of Rodgers and Edwards was palpable. More significantly, C’est Chic and Chic’s music laid groundwork for the emergence of hip-hop and house music. In the Bronx, the earliest hip-hop DJs in 1979 were looping Chic’s basslines (most famously “Good Times” from the Risqué album, but “Le Freak” was reportedly also spun at block parties). The groove-centric nature of Chic’s tracks made them perfect for rap MCs and DJs – as noted in one commentary, “from new wave to hip-hop to house, it is amazing how many people were affected by the distinctive Nile Rodgers/Bernard Edwards sound”. While “Good Times” (1979) had the most famous hip-hop sample via Sugarhill Gang, C’est Chic’s “Le Freak” and “Savoir Faire” also found their way into later hip-hop tracks (MC Lyte, for example, sampled “Le Freak” in 1998 , and various producers have lifted riffs from the album for beats). In Chicago and Detroit, early house music producers revered Chic’s records; the deep house legend Moodymann notably sampled “I Want Your Love” in his track “I Can’t Kick This Feelin’,” basically constructing a new house groove from Chic’s blueprint. This shows how C’est Chic directly seeded ideas in emerging genres beyond disco.

Beyond samples, the aesthetic legacy of C’est Chic is evident. The album’s French title and sophisticated imagery (the very name “C’est Chic” implying high style) helped cement the idea of disco as not just party music but a lifestyle of elegance and glamour. Chic’s approach influenced countless artists who wanted to combine style with sound – for instance, the New Romantic and upscale funk artists of the ’80s (like Duran Duran, who cited Chic as an influence, and whose bassist John Taylor idolized Bernard Edwards’ playing). The resurgence of disco/funk elements in later decades – whether the French Touch house music of the ’90s (Daft Punk, etc.) or the disco-pop revival of the 2010s – continually points back to Chic’s catalog. It’s telling that Nile Rodgers became a go-to collaborator in the 2010s for modern acts wanting that authentic funk magic (e.g. Daft Punk’s 2013 hit “Get Lucky” featuring Rodgers, which is steeped in Chic-like guitar groove). Those collaborations often included live performances of “Le Freak” or nods to Chic songs, reintroducing C’est Chic’s music to younger audiences.

Culturally, “Le Freak” in particular has an outsized legacy. The phrase “Freak Out!” entered the vernacular; even people who might not know Chic recognize that rallying cry. The song is frequently used in films, TV, and advertisements to instantly evoke the late ’70s disco vibe – it’s practically shorthand for the era’s joyous excess. In 2018, Billboard ranked “Le Freak” among the top songs in its all-time charts (it was #21 in Billboard’s list of top songs of the first 55 years of the Hot 100) , underlining its long-term popularity. Meanwhile, C’est Chic as an album often appears on “essential albums” lists, and was included in the reference book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, which praised it as “one of the last great dance records before the machines took over” in the 1980s. That quote highlights how Chic’s human touch – the live bass, guitar, and orchestration – marked the end of an era, right before drum machines and synths began to dominate dance music.

The album’s legacy also includes the role it played in disco’s climax. Coming out just a year before the anti-disco backlash, C’est Chic enjoyed the genre’s final glory days. When the disco backlash hit (and Chic’s fortunes briefly fell in the early ’80s), the album became a time capsule of the optimism and creative peak of that movement. Over time, as the stigma around disco faded, C’est Chic has been celebrated for its artistry. The fact that Chic’s music was later re-evaluated by rock critics and inducted into halls of fame (e.g., “Le Freak” in the Grammy Hall of Fame , and Chic’s influence acknowledged by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Nile Rodgers’ award) speaks to the album’s enduring impact. In clubs and weddings alike, “Le Freak” continues to get people of all ages dancing, and “I Want Your Love” remains a staple on disco playlists. In sum, C’est Chic not only encapsulated the zenith of disco’s commercial and creative run, but it also planted seeds that would germinate in various corners of music – from R&B to rock to electronic – making its influence truly cross-genre and cross-generational.

Critical Reception

Upon its release in 1978, C’est Chic received a mixed but generally positive reception from critics – reflecting, in part, the divided views on disco at the time. Many in the mainstream music press were skeptical of disco’s artistic value, yet Chic’s obvious musical chops and polished production earned respect from some quarters. For instance, The Globe and Mail praised the album as “a sleekly elegant variation of disco”, suggesting that Chic had elevated the form with sophistication. This reviewer recognized that Rodgers and Edwards brought a level of finesse in songwriting and arrangement that set the album apart from generic dance records. On the other hand, The Los Angeles Times was more dismissive, opining that aside from the blockbuster “Le Freak,” the rest of the album “consists of pedestrian disco pieces and plodding R&B ballads”. That critique specifically knocks the non-singles (likely targeting tracks like “Happy Man” or “At Last I Am Free”), implying they found them unremarkable. It’s worth noting that such a view might have been colored by a general rock-critic bias against slower or subtler disco tracks, as “pedestrian” and “plodding” are harsh words for what others later appreciated as nuanced songs.

One influential critic, Robert Christgau, gave C’est Chic a lukewarm review in his Consumer Guide, grading it a “B.” Christgau quipped that “the hooky cuts are more jingles than songs, the interludes more vamps than breaks” – an acknowledgment of Chic’s repetitive, groove-oriented formula. He half-jokingly added, “I won’t dance, so don’t ask me. Well, maybe if you’re really nice.”, indicating that even a self-professed non-dancer found some charm in the music. In summary, Christgau found the album catchy but somewhat insubstantial, yet he couldn’t entirely resist its pull. This encapsulates a common critical stance at the time: grudging admiration.

Despite some ambivalence in 1978–79 reviews, the sheer popularity of C’est Chic was impossible to ignore. Major music publications noted the hit singles; Rolling Stone magazine, while historically not very kind to disco, acknowledged Chic’s knack for groove. (Years later, Rolling Stone would include Chic’s work in retrospective praise, but contemporary coverage was limited.) Some critics outside the U.S. were more enthusiastic – for example, in the UK, where Chic had a strong following, reviews highlighted the album’s blend of American funk and European style. Melody Maker and NME tended to view Chic favorably as artists within disco.

Over the decades, C’est Chic’s critical reputation has grown significantly. Retrospective reviews often hail it as Chic’s finest album and a classic of late-70s pop music. For instance, AllMusic later gave it a glowing assessment (AllMusic’s editors rate it highly, pointing out how it “put Chic at the top of [disco]” with its “pair of dancefloor anthems” ). In the 2000s and 2010s, publications reappraising disco have been far kinder. Pitchfork, in a review of Chic’s reissues, scored C’est Chic an 8.4 out of 10, indicating strong acclaim – quite a turnaround from the skepticism of 1979. The Spin Alternative Record Guide (1995) even rated it 9/10 , showing the album had by then earned cred among rock and alternative critics as well. Writers frequently laud the album’s consistency – how it “plays like a greatest hits compilation” with no filler – and commend Rodgers and Edwards’ production as groundbreaking. The inclusion of C’est Chic in the 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die compendium came with high praise: “This disco didn’t suck,” the entry declares bluntly, celebrating the album’s cool precision and claiming it “was one of the last great dance records” of its era. Such retrospective voices counter the old prejudices and assert the album’s artistic value.

In summary, at the time of release C’est Chic was respected for its hits and polish but faced some critical snobbery (common for the genre). However, history has vindicated Chic – today, critics view C’est Chic as an essential album of the late ’70s, praising its craftsmanship and influence. The contrast between initial and later reviews is stark: what one paper dismissed as “pedestrian” has since been recognized as pioneering and expertly executed. The album’s critical legacy, therefore, is one of elevation – rising from a perceived disposable dance record to a canonized classic in pop music history. And of course, the enduring critical metric is influence: C’est Chic influenced so many artists that its critical stock only grew as those artists (from Duran Duran to Daft Punk) cited Chic as inspiration, prompting new examinations of Chic’s discography in a positive light.

Notable Covers & Samples

The songs of C’est Chic have inspired numerous cover versions and samples, underlining the album’s far-reaching influence. Here are some of the most notable examples:

• “Le Freak” – Covers & References: Surprisingly for such a famous song, straight covers of “Le Freak” by major artists are few (perhaps because Chic’s original is hard to top). However, Chic themselves revisited “Le Freak” in various live performances and mixes. In 1987, a remixed version titled “Jack Le Freak” – giving the song an acid-house twist – was released and reached #18 on the UK charts . This remix by Phil Harding brought “Le Freak” into the late-80s club scene, and was actually Chic’s last Top 40 hit in the UK. In terms of samples, “Le Freak”’s signature lines and groove have popped up in other works. Hip-hop artist MC Lyte sampled the song in 1998 on her track “Woo Woo (Party Time),” which lifted the “Freak out!” hook and Chic’s music for a 90s party anthem . The song’s central bassline and guitar riff have been referenced by DJs over the years, and its title itself has been name-checked in lyrics by various artists celebrating disco. Additionally, “Le Freak” is frequently interpolated in medleys by funk/R&B bands; even Prince worked a bit of “Le Freak” into live jams, acknowledging its iconic status.

• “I Want Your Love” – Covers: This sultry track has seen high-profile covers, especially in the 21st century. R&B/dance singer Jody Watley recorded a faithful cover of “I Want Your Love” in 2006 for her album The Makeover. Released as a single in 2007, Watley’s version (produced by DJ Spinna) was a hit on the dance charts – it reached #1 on Billboard’s Dance/Club Play chart in June 2007. Watley’s take paid homage to the Chic original while updating the production for modern clubs, and its success showed the song’s enduring appeal. An even splashier cover came from pop superstar Lady Gaga. Gaga teamed up with Nile Rodgers in 2015 to record “I Want Your Love” for a Tom Ford fashion campaign video. In this version, Gaga lent her powerful vocals to the track and Rodgers re-created the funky guitar magic. The music video, essentially a stylish runway montage, featured Gaga’s cover as the soundtrack, described as a “jazzy spin” on Chic’s classic. The cover generated buzz online and introduced the song to many of Gaga’s young fans. (A studio version of Gaga’s “I Want Your Love” was later included on a Chic compilation in 2018.) Beyond these, the song has also been covered in live settings by various artists; for instance, British soul singer Seal has performed “I Want Your Love” on stage with Nile Rodgers at tribute events. The track’s potent combination of strings and grooves makes it a favorite for reinterpretation.

• “At Last I Am Free” – Covers: Perhaps the most artistically significant cover from this album is Robert Wyatt’s 1980 version of “At Last I Am Free.” Wyatt, a revered figure in progressive rock and jazz circles, took this deep Chic cut and transformed it. His cover is sparse and haunting – just Wyatt’s fragile voice and minimal instrumentation – highlighting the song’s emotional core. Released as a single on Rough Trade, it was a bold song choice for a political avant-garde artist, but it worked: one critic noted Wyatt brought “heartbreaking honesty” to it, making it an “anthem for the turning of a page” with its open-ended lyrics about freedom. Wyatt’s cover gave the song a cult following outside the disco context and is often cited as proof of Rodgers and Edwards’ songwriting depth. Other artists followed suit. Elizabeth Fraser, the ethereal-voiced singer of Cocteau Twins, covered “At Last I Am Free” for a 2003 tribute, also emphasizing its dreamy, sorrowful qualities. Indie artists like Everything But The Girl (Ben Watt) and others have performed it live. More recently, singer Blood Orange (Dev Hynes) and jazz vocalist Cassandra Wilson have referenced or covered the song, drawn by its sublime mood. These covers, spanning genres from post-punk to folk to jazz, underscore how “At Last I Am Free” resonated far beyond disco – it became something of a standard for conveying bittersweet liberation.

• Samples in Hip-Hop and Dance Music: Beyond explicit covers, C’est Chic has been a fertile source for sampling. “Good Times,” though from the next album Risqué, is famously Chic’s most-sampled track (Rapper’s Delight, etc.), but C’est Chic has its share. “I Want Your Love” in particular is a crate-digger’s delight: its intro and breakdown have been sampled in at least dozens of tracks. The French house duo Daft Punk were heavily inspired by Chic; there was even discussion that their track “Revolution 909” was built around an “I Want Your Love” sample (a theory among fans ). Detroit house producer Moodymann sampled “I Want Your Love” extensively in “I Can’t Kick This Feelin’,” looping the bass riff and vocal fragments into a deep, hypnotic groove – essentially a love letter to Chic’s original. Hip-hop and R&B acts have also dipped into the album: for instance, Mariah Carey’s 1999 hit “Heartbreaker” (Remix) interpolated elements of “Attack of the Name Game,” which itself was built on the “I Want Your Love” bassline – a kind of second-generation sample. “Savoir Faire,” with its smooth instrumental groove, attracted rappers; it was sampled by Grand Puba and by Rick Ross (in the track “Hit U From the Back” ) as a backdrop for rhymes that needed a laid-back cool. Even “Chic Cheer”’s drum fill or groove has been scratched into DJ sets. These samples pay tribute to Chic’s immaculate grooves, and because Rodgers/Edwards were such skilled writers, their bass lines and riffs can be lifted and still carry a track decades later.

• Live Tributes and Medleys: In addition to formal covers, many artists have performed C’est Chic songs live. Chic’s contemporaries like Sister Sledge (whom Rodgers/Edwards produced) sometimes included bits of “Le Freak” in their concerts. In recent years, Nile Rodgers – as bandleader of the reunited Chic – often collaborates with younger artists on stage. For example, at the 2013 Montreux Jazz Festival, Rodgers jammed “Le Freak” with musicians from across genres, and in 2017 he joined DJ duo The Martinez Brothers for a modern remix of “I Want Your Love.” The presence of C’est Chic songs in DJ sets, remix projects (notably Dimitri From Paris’ remixes of Chic tracks ), and tribute concerts (such as the Songwriters Hall of Fame honoring Rodgers/Edwards) continually refreshes these songs for new audiences.

In summary, the music of C’est Chic has proven highly transmutable – whether in covers by artists as varied as Lady Gaga and Robert Wyatt, or in sampled form within house, hip-hop, and pop songs. Each new iteration, from Watley’s club hit to Gaga’s fashion video and countless DJ re-edits, reinforces the album’s status as a wellspring of inspiration. These covers and samples are not only a nod to Chic’s songwriting brilliance but have also helped keep the album’s legacy alive in public consciousness over the decades.

Interesting Facts & Trivia

Beyond the music and charts, C’est Chic comes with an array of fascinating stories and tidbits. Here are some interesting facts and trivia about the album and its creation:

• Studio 54 and the Birth of “Le Freak”: Perhaps the most famous anecdote is how “Le Freak” got its start. After Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards were barred from entering Studio 54 on NYE 1977 (despite being invited by Grace Jones), they turned that frustration into creativity. Jamming at home, they originally riffed on the phrase “F** off!” to mock the club doorman . Realizing the potential of the groove, they mutated “f** off” to “freak out” and wrote a full song around it – a prime example of artists turning a sour incident into a sweet hit. The title “Le Freak” itself was a clever twist; Rodgers has said they liked the chic sound of French (the band already had a Francophile bent with its name and aesthetic), so they named the song with a French article to match C’est Chic’s vibe. What began as a private joke became a public catchphrase and the band’s biggest hit. As a final twist, Studio 54 eventually embraced the song – it became an anthem at the club it was born from, and Chic later got their vindication by performing there to a packed crowd.

• Atlantic’s Best-Selling Single: “Le Freak”’s success was not just personal for Chic; it was a milestone for their record label. The single became the best-selling 45 RPM single in Atlantic Records history. Considering Atlantic’s storied roster (Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Led Zeppelin, etc.), this was a huge deal. That record stood for many years; it’s often cited in music trivia that “Le Freak” outsold even big rock singles on Atlantic. It held the title until possibly dislodged by another blockbuster in the ’80s, but it cemented Chic’s place in label lore.

• Album Title and Artwork Changes: C’est Chic was originally planned to be released in Europe under a different name – Très Chic (French for “very chic”). In fact, the initial European edition carried the title Très Chic and had an alternate cover featuring a risqué photo of a model wrapped in a transparent tube of neon light . This cover was deemed too suggestive and was quickly withdrawn. Atlantic’s European branch reissued the album with the standard C’est Chic title and a tamer cover (the U.S. artwork, which features the band’s name and album title in a stylish layout with a model, much more in line with the band’s classy image). Additionally, the Très Chic version had a different track listing: it notably inserted Chic’s prior hits “Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)” and “Everybody Dance” into the running order – likely to market the album with more hit songs. After the recall, C’est Chic in Europe matched the U.S. tracklist. Today, Très Chic vinyl pressings with the original cover are collectors’ items, and the incident is a quirky footnote in the album’s history showing how marketing strategies differed by region.

• Personnel Nuggets: C’est Chic had some notable contributors. Luther Vandross, who later became an R&B superstar, is credited as a background vocalist on the album. Vandross was part of Chic’s circle in the late ’70s, often singing on Chic Organization projects (he’s also on Sister Sledge’s We Are Family). His smooth tenor can be heard in the rich vocal harmonies, an early career footnote before his solo fame. Another famous name: Bob Clearmountain, the recording/mix engineer for C’est Chic , went on to become one of the top engineers/producers in rock (working with Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones, etc.). His work on Chic’s records, getting that perfect drum and bass sound, was some of his breakout engineering work. And then there’s Gene Orloff, a renowned violinist who served as concertmaster for the Chic Strings – Orloff was a seasoned arranger who had worked with everyone from Billie Holiday to James Brown. Chic brought in these A-list session players to elevate their sound. Even top jazz trumpeter Jon Faddis lent his chops on trumpet – a sign of how respected Rodgers and Edwards were that such talent participated in a “disco” record.

• Parallel Projects – The Chic Organization’s Busy 1978: While Chic were making C’est Chic, Rodgers and Edwards were also writing and producing for other artists. In the same timeframe, they crafted Sister Sledge’s album We Are Family (released in early 1979), which yielded hits like “He’s the Greatest Dancer” and “We Are Family.” The creative energy was flowing; legend has it that “He’s the Greatest Dancer” was originally intended for C’est Chic but was given to Sister Sledge instead. Additionally, former Chic singer Norma Jean Wright (who sang on Chic’s debut album) recorded her solo album in 1978 with Rodgers/Edwards producing – her single “Saturday” was a minor hit. This illustrates a trivia point: the C’est Chic sessions were part of an incredibly prolific period for Rodgers and Edwards. They were essentially running their own mini-Motown, using the Chic sound across multiple projects. This can be felt in the confidence and quality of C’est Chic – the team was in top form.

• Accolades and Lists: In later years, C’est Chic and its tracks have accumulated accolades. Besides the aforementioned Grammy Hall of Fame induction for “Le Freak,” Rolling Stone ranked “Le Freak” on its list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time (in the 2021 update, it was included, reflecting its lasting importance). The album itself often appears in best-of lists: e.g., Slant Magazine placed C’est Chic high in its “Best Disco Albums” ranking, and Pitchfork included C’est Chic in a feature of “favorite albums of the 1970s,” giving it that 8.4 score and noting Chic’s influence on modern dance punk and pop . Such trivia bits highlight that what was once seen as disposable dance music is now archived in the pantheon of great music.

• Phrase Origins – “Chic Cheer”: Another fun tidbit is the track “Chic Cheer” includes the chant “Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah,” which is also heard in Chic’s earlier hit “Dance, Dance, Dance.” This phrase was a catchphrase taken from 1930s dance marathons (popularized by a radio MC of that era). Chic liked to repurpose vintage dance idioms (another nod to their sense of style and history). “Yowsah” appearing in Chic songs is a bit of self-referential fun – by C’est Chic, it served to tie their new material back to their debut hit, almost like an easter egg for fans.

• Modern Rediscovery: A recent interesting footnote – in 2018, to celebrate the album’s 40th anniversary, Atlantic Records did a special remaster at Abbey Road Studios in London . The remaster brought out even more clarity in the tapes, and audiophiles noted how C’est Chic sounds remarkably fresh. Nile Rodgers, still active, often remarks in interviews how proud he is of C’est Chic. In 2019, he curated a playlist for BBC and included multiple C’est Chic tracks, reminiscing about their creation. Such events show that the album continues to be cherished and examined long after its original run.

In closing, the lore around C’est Chic – from the fateful Studio 54 incident to the withdrawn European cover and hidden track – adds color to what is already a landmark album. These stories and trivia not only serve as fun facts for fans but also underline the cultural moment into which Chic’s music was born. The album’s mix of glamorous image, behind-the-scenes drama, and sheer musical brilliance make C’est Chic a rich subject for both the casual listener and the music historian. It’s an album with plenty of stories to tell – all befitting a record that truly lived up to its name in being, indeed, chic.

Sources: Historical and chart information from Billboard, RIAA, and BPI certifications ; album personnel and production details from the C’est Chic liner notes and Wikipedia ; background anecdotes from interviews and retrospectives (e.g., Rhino Records’ album notes ); critical quotes from contemporary reviews in The Globe and Mail and Los Angeles Times , Christgau’s Consumer Guide ; retrospective commentary from 1001 Albums analysis and Subjective Sounds review ; cover and sample information from Billboard and artist interviews (e.g., Jody Watley’s chart achievement , Lady Gaga’s cover details in Entertainment Weekly , Robert Wyatt cover context from The Guardian/Wyatt interviews ).